The Rocks Aboriginal Dreaming Tour

I easily spot our tour guide for The Rocks Aboriginal Dreaming Tour. Wearing a black jacket, the sleeves decorated with yellow dots and spirals, she’s standing under a tree chatting to guests. Donia “as in the last part of Caledonia,” she explains, has short cropped bleached blonde hair and an easy smile.

Where’s the Map

Welcoming people as they arrive, Donia makes a point of memorizing each person’s name. On the dot of 10:30 she takes a short fat stick out of her backpack, saying that she’ll “start with the map.”

At first, I’m confused. There’s no map. Instead, as she leads us to the sandy forecourt between Cadman’s Cottage and the Harbour Foreshore, Donia tells us that she’ll be sharing Aunty Margaret’s Dreamtime Story.

Aunty Margaret Cambell

Donia has worked for Aunty Margret for “about seven years.” Aunty Margret Campbell, now in her 70s, began her Cultural Tourism business back in 1993, sharing her story and cultural knowledge. She renamed her business Dreamtime Southern X in 2012.

Acknowledging the Gadigal people who took care of and have been the custodians of the land where we stand, Donia explains that they were one of 29 clans who formed the Greater Eora Nation. As she speaks, she bends down and uses her stick to draw in the sand.

Drawing the Map

Joking that “I can’t draw, she begins by drawing a jagged line representing the Blue Mountains, followed by the rivers that bound the area. There’s Deerubbin, or the Hawkesbury River to the north; the Yandhai or Nepean to the west, the Burramattagal (place where Eels lie down) or Parramatta River and the Tucoerahor (Georges River) to the south.

Depending on where they lived, they were fresh water people, mountain people or salt water people. “We are salt water people,” Donia adds.

Drawing interconnecting circles, Donia describes how the groups interacted, and how over time, people would travel around the boundaries of all the clans, gaining knowledge along the way.

We lean forward to look at the map. The circles, lines and dots are clearly recognizable as an Aboriginal drawing. “I have become an artist after all,” Donia jokes as she scrubs out the map with her feet.

Clapsticks

Taking a pair of clapsticks out of her bag, she claps them rhythmically as she acknowledges Earth Mother, “a common courtesy,” she says.

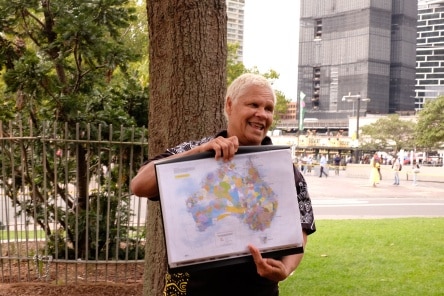

Holding up a map of Australia’s Aboriginal tribes, Donia points first to the area where Sydney would be on the map. “This little green dot is where 29 tribes lived,” she says. To the west of the Blue Mountains is the largest area, the land of the Wiradjuri Nation.

Donia neither shies away from colonial history, nor does she labour the point. She describes what happened and moves on. Her grandmother was from K’gari, the now recognised name for Fraser Island. During white assimilation she was “put on a ship and taken to Cairns.”

Attuned to the Environment

At the base of a young casuarina tree, Donia explains how her people were “attuned to the environment.” The tree, a nursery tree, provided children with shelter as they waited in the shade. Using photographs to illustrate her story, she describes how the bark of a tree could be used as to make a coolamon which, lined with a possum skin, could be used to hold a young baby.

Saying with a big smile, “I love us sharing our culture together,” she takes a possum skin from her bag. It’s the skin of a brushtail possum. I press my hand into the thick soft fur, fascinated to learn that as the child grows, skins are added, their story etched on the inside of the skin.

Now I understand why some Indigenous parliamentarians have worn a possum cloak when inducted into parliament.

Learning from Nature

Gently rubbing the trunk of a cabbage tree, Donia draws our attention to the thin parallel vertical and horizontal lines forming a pattern on the bark. The tree sheds a fibrous material that women used to use to make bags. It also provides shelter and food. “Very talented,” says Donia.

Next, she’s leaning into the centre of a large strappy plant, pulling at the long strappy green leaves. She hands a couple out, encouraging us to taste the white ends. I can’t taste anything, but others detect radish or celery.

My mouth fills with saliva. Donia explains that on a hot day, thirsty Aboriginal people will bite on these leaves to activate the salivary glands. The leaves are also used to weave mats. I follow her lead, using my nail to split the strong leaf into four narrow strands and make an attempt to weave them. Women also painted with the leaf’s soft end and ground the plant seeds into flour.

Donia draws people to her with her enthusiastic smile and gentle manner. She explains how her people learn from nature adding that “Aunty Margret likes to tell people that ‘by the time your’re 12, you have a doctorate.’”

Trespassers in our Own Land

We cross George Street to walk into The Rocks, stopping in a small courtyard. Here in this area, with its sandstone buildings, Donia talks briefly about displacement. How her people were moved from their land, and were dying as their food sources were taken away. “We became trespassers on our own land,” she says, and “Over time we adopted wearing clothes and eating refined European food.”

Middens

Changing the subject, she says “I want to talk about middens,” emptying a small pile of shells from a blue cloth bag onto floor. “I ate these guys,” she says pointing to grey rounded periwinkles. “They’re Aunty Margret’s totem. She can’t eat them, but I can.”

Midden sites helped people to navigate and find food sources. They indicated what was available to eat in the area. Bennelong point was one of many midden sites in the area. When colonists arrived, they crushed the shells found in middens for lime when building the colony. Donia points to white fragments of crushed shell in the mortar used to build the sandstone wall behind her.

Ochre

Donia leads us through a corridor between two shop doors to a section of sandstone cliff. She stands in a hand cut metre deep wide alcove. Swirls of white colour the rock behind her. Gently wiping the fingertips of her right index and middle fingers across the edge of one of the swirls, Donia removes a little ochre, saying “I try not to tamper too much.” She demonstrates how the ochre is used to paint white lines on her dark skin.

Ending The Rocks Aboriginal Dreaming Tour

The tour ends with a roar. Taking a bullroarer from her bag, Donia co-opts one of the men in the group to whirl the carved elongated wooden oval around his head. His efforts don’t pay off. Another man has better luck, producing a whoop whoop roar as the ‘instrument’ whirls around his head.

Donia packs her bag, smiles, thanks us individually by name for joining her on The Rocks Aboriginal Dreaming Tour. Within minutes she disappears into the stream of Saturday morning visitors to The Rocks.

Useful Information

- Find out more about this tour here

- For other tours of The Rocks, read about a Ghost tour here and a Bar Tour here (there are three different bar tours, one in The Rocks)

- Here’s a post of mine about walking through The Rocks independently

Lovely, I must do this one day.

You’d enjoy it, Seana

This is so interesting! I love the part about the possum skins being added to over the years.

Yes, I enjoyed discovering more about Aboriginal culture.

What a wonderful tour! Next time I’m in Sydney I will go.

I don’t think you’ll be disappointed, Erica

Thanks Joanne didn’t know this tour existed. You do some interesting tours love reading about them.

Maura

Thanks Maura, I pretty much stopped ‘discovering suburban Sydney’ after walking and writing about over 80 suburbs. Now, I join tours that interest me and add to my knowledge about the wonderful city I live in. I am pleased you enjoy reading about them.

Thanks Joanne. I’ll do this tour before the end of the year. It seems to me so important to continue and enhance the communication between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures residing in Sydney (and throughout Australia). Tours like this are a great way to nurture understanding between people of different cultures. – those who arrived really quite recently and those who looked after the land for thousands of years before that.

Dale

How well you put that, Dale. Thank you.

It’s the same sad story around the world, where indigenous people are removed from their ancestral homes.

It doesn’t make up for the harm caused, but at least now people are reclaiming their culture and sharing it with those willing to listen. And increasingly, people are listening.